- Home

- Gareth Rubin

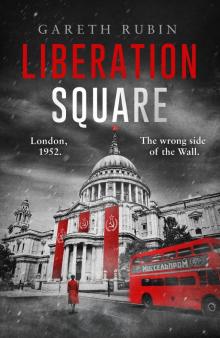

Liberation Square

Liberation Square Read online

Gareth Rubin

* * *

LIBERATION SQUARE

Contents

Maps

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chronology

Historical Notes

Acknowledgements

Follow Penguin

For my parents, a psychologist and a historian

1

We walked all the way to Checkpoint Charlie that day. At the end of the road, the grey autumn light made the barbed wire and the concrete guard towers disappear into the sky, so that you could believe they kept on rising forever. I stood watching crowds of people stare at the only opening in the Wall for twenty kilometres, and tried to pick out those who had come for a day trip just to gaze at it from the locals who could remember it being built and still felt the loss. But the faces all showed the same mix of anger and quiet sorrow.

The soldiers in their muddy-brown uniforms looked bored as they paced back and forth between the metal barriers. They always look bored. I once saw one grinning and winking at the girls in the crowd, but he was the exception – they stand there for six hours straight, rain or shine, and you wonder if they hope for the occasional attempt to jump the Wall, or an attack by the Western Fascists, just so they can put their training into practice. Even I, when I had a gun placed in my hands for my Compulsory Basic, felt a bit of a thrill as I pulled the trigger. The kick from the Kalashnikov nearly knocked me over, though, and my instructor laughed before taking it from me and replacing it with a single-shot rifle.

So the boys in the watch towers were looking for a spark of excitement while the people below were looking for some sort of understanding. They wouldn’t find any there, I knew.

Nick appeared through the crowd then, carrying the drinks that he had bought from a man with a cart. He handed one to me, and we both turned to silently gaze at the barrier.

‘What do you think, when you look at it?’ he said after a while.

My eyes ranged over the barbed wire and thick camouflage netting that prevented you from seeing through the ten-metre opening in the concrete. ‘I suppose it’s hard to put into words,’ I replied. ‘It feels like we’ve lost something, something we won’t get back. But, well, maybe it’s necessary, just for now.’

He peered up at the guard tower. ‘So they say.’

A group of schoolboys shuffled past, clutching the red paperbacks that were to be the map to our future. One broke off and wandered right up to the soldiers, but his teacher caught him and dragged him away, to the laughter of the others. They were just like the ones that I used to teach. I suppose children are the same everywhere.

‘Do you remember it going up?’ I asked.

‘Vividly,’ Nick said. ‘Yes, vividly.’

I understood and twisted his warm fingers into mine. After five months of marriage I could recognize the ridges and wrinkles in his skin. ‘At least we’re on the same side of it.’

‘Yes. That’s something.’ He sighed. ‘I do have friends over there, though.’

I looked over at the guards, wondering what they were thinking as they stared back at us. It must all have seemed very different to them. Perspective changes things. ‘I expect you’ll see them again. They might be on the other side right now, looking this way.’

‘Perhaps.’

A man approached the schoolboys, offering photographs of the Wall to be used as postcards. ‘Strange things to send,’ I said.

‘Presumably you give them to people you don’t like.’ I smiled.

The school party stopped in front of a hoarding showing the country split in half, with ten occupied babies’ cots on the other side, and nine on ours alongside an empty one bearing the slogan YOUR CHILD. STRENGTH IN NUMBERS! The boys’ teacher reached into his briefcase, took out another copy of the red book, in which the First Secretary had set out our nation’s course, and began to read out a passage.

Nick nodded in his direction with a sceptical smirk. ‘Does he think it’s all going to work so beautifully?’ he said.

I glanced around to make sure we couldn’t be overheard. ‘Well it’s worth trying, isn’t it? Surely if the state makes certain everyone is fed and has a job, nine tenths of all the fights and arguments we have with each other will be gone.’ And really it did make sense – God knows there were difficult aspects to our new life, but the argument seemed entirely logical, and rehearsing it in my mind made me hopeful for the future.

‘Overnight. In a puff of smoke.’ He tried to suppress a smile.

‘Oh, you’re a horrid man.’ I poked him in the ribs. ‘So what’s your big idea, then?’

‘I’m glad you asked,’ he said. ‘A gliding wing.’

‘A gliding wing?’

‘That’s it. We build it on the roof in the dead of night, wait until the wind picks up, then soar over the Wall like a couple of birds. Down a pink gin and slip into the best hotel we can find for an hour.’ He did some calculations in his head. ‘Make it ninety minutes.’

‘You need a cold shower.’ But my hand slipped around his waist.

‘Maybe I do.’ A soldier crossed from one side of the watch tower to the other, scanning the crowd with his binoculars. ‘Awful job,’ Nick said.

‘People surprise you. What they can do.’

‘That’s true. That’s always true.’ Above us a flock of black birds drifted so high that they became specks of dust. ‘Shall we go?’

I nodded. ‘Yes, let’s.’

As we left, north towards Oxford Street, I gazed back at the statue of Eros, his attempt to leap over the Wall permanently frozen, caught by the concrete and the wire.

2

In my very soul I believe that there is nothing on this earth as wonderful as the land we have inherited from our forefathers. Tomorrow we will mark seven years since the shining Archangel sailed up the Thames to liberate us from Fascism. In those seven short years we have sown the seeds of peace to realize the promise of our ancestors. Capitalism, you see, sees greed and mutual mistrust as the most desirable of human attributes. Communism answers that claim with a belief in the fundamental goodness of humanity. And we have believed it for a very long time – for what was the cry of the French Revolutionaries? Liberté. Egalité. Fraternité. Now I won’t paint a rosy picture of the future. At times it will be difficult. But some day we will be truly free, and that means living in equality and brotherhood.

Anthony Blunt, interviewed on RGB

Station 1, Monday, 17 November 1952

A few weeks later, I walked the same route north to Oxford Street, part of a mass of people trudging slowly with scarves or cotton masks tied over their mouths to keep out the heavy November smog. The few cars on the road sprayed one by one through the gutter, so that regular waves of oily water swept

on to the pavement, leaving pools clouded with dirt. It had been less than a month since that day, but so much had changed.

I stopped to look down Regent Street. With their faces covered, the swaddled bodies seemed like a strange crowd of moving shop mannequins, reeling about on the pavement in patterns only they understood. Someone’s shoulder knocked into mine and a man in a raincoat seemed to mumble an apology through his scarf, but before I could say anything he had melted into the throng, disappearing among countless others shambling in every direction. I took a moment to wipe the grime from my face before I set off again.

Along the way, I peered into the shop windows. Some were well stocked with winter clothes that could keep the cold out and the warm in. My shoes would do for another year, but I needed a new pair of leather boots and I hoped Nick could find me some. One of his patients could get hold of good clothes – the yellow woollen overcoat he had somehow come up with was the best I had ever had. Even before the War, I could barely have afforded it and there was certainly nothing in the shops now that came close. I thought about asking if he could buy another one and keeping it in a box until needed – you never knew when you would see anything like that. Nick said the man had connections with the factory, that’s how he had first go at what they turned out.

Looking in one misted window, I found myself staring into a baby-goods store. Its sole display was a wooden cot, painted bright pink for a girl and my eyes traced the delicate flowers etched up its sides. But then the migraine that I had felt brewing all morning seemed to worsen and I knew that I needed to sit down and let it pass. I thought of the little café around the corner where the coffee was ersatz but the staff were friendly and didn’t bother you if you ordered something small from time to time. The owner was a plump and matronly woman who seemed to treat customers like members of her family who had dropped by for a chat, and she served little scones for five new pence, which was good value. ‘All I can charge, love,’ she had told me, although I didn’t think that was true. They were edible too, unlike what was offered by some of the places around there. Or Nick’s surgery wasn’t far – I could go there instead and sit in one of the soft armchairs and he would tell me a silly joke he had heard that day, busying himself while I let the pain subside.

‘Are you just going to stand there?’

I looked around to see a cheaply dressed woman my own age staring at me. ‘Sorry,’ I said, my cheeks flushing red as I stepped aside to let her enter the shop. ‘Miles away.’

‘Hard enough as it is,’ she muttered. ‘Probably nothing in there anyhow.’

‘Oh, I’m sure there will be.’

She looked at me as if I were an idiot. ‘And you would know all about it, would you?’

‘I mean –’

‘Don’t matter what you mean, do it?’

She pushed past me into the store and I blushed again, embarrassed, before hurriedly edging into the flow of muffled people descending the steps into Oxford Circus Tube Station.

The concourse wasn’t too bad, but when I got to the Oxaloo Line platform I found it so packed that I thought I would never get on the train, and the closeness of the coughing bodies and lack of air made my head worse. As the carriages came to a halt, we all shoved in, staring straight ahead, not speaking to each other, and I only just managed to get on. While we shuffled around, my eyes fell on a poster above the seats, warning of the threat of infiltration, showing tunnels burrowing from the DUK land – everything north of a line stretching from Bristol to Norfolk, plus the north-western quarter of London – into our Republic of Great Britain, covering southern England and the rest of the capital. Constant vigilance was needed, it said. Then a man pushed in front of me, blocking my view of the poster.

The train started up and rattled away from the now-deserted platform. They say that during the Blitz, the men and women who used the Underground as a shelter at night would just take themselves off to quiet corners without even knowing each other’s names. No doubt, thinking you might get blown apart as soon as you set foot above ground makes you realize that there are some things you don’t want to go to your grave never having tried. And I think it was seen as patriotic too if it were some young man being sent to the front who might never come back – to give him something to smile about when he was on the ship going over.

Not many did come back, of course, and I knew some of those who didn’t: boys I had grown up with and would never see again except in my mind’s eye. I had held those sickness-inducing photographs of the D-Day beaches, though – countless bodies with their heads or limbs missing. Tens of thousands of corpses floating in the water. The Germans had taken a lot of images to celebrate how victorious they had been over us. Then, after the Red Army had, in their turn, defeated the Germans, we had been shown those images to learn how lucky we had been that the Soviets had come to our aid. Either way, the photographs had left me feeling ill for a very long time.

After forcing my way out at Waterloo, I passed the broken remains of Westminster Bridge that invited you to step off the bricks and into the river. That’s if you could somehow scale the electrified wire and stay hidden from the guard towers and their searchlights, of course. Everyone had heard of someone who had managed it, but the stories were always second-hand, and there was a line of simple white crosses on the other side for those who had slipped silently into the black water at night and tried without success.

As I walked, the paving stones echoed to the sound of Comrade Blunt’s daily radio address leaking from a government building. He was speaking of the new day ahead of us: a day of peace and plenty. My footsteps rang in unison with his words as I passed the gloomy block, followed by sparsely stocked grocery shops, a pub or two, and little tobacconists.

And then, finally, Nick’s surgery shifted into view, at the top of one of the old Georgian blocks on the south side of the Thames, opposite the Houses of Parliament.

From his consulting room, you could see Big Ben – or what was left of it. The glass had been smashed out of the four clock faces, leaving ugly dark holes like blinded eyes. Apparently the Luftwaffe had shot them to pieces as they scented victory over us and there was no more RAF to stop them – it must have been nothing but sport to them then. Below the tower, most of the Palace of Westminster still stood, but the far end had been turned to rubble in the final battle and no one had rebuilt it. And, in front of it all, the American ‘protection troops’ stood along the river with their rifles pointing at us. It was that sight, more than any other, I think, that seemed to sum up for me what extremities our nation had been forced into.

‘Good afternoon, Mrs Cawson,’ Mr Paine, the ageing porter, greeted me from his chair just inside the building entrance.

‘Good afternoon.’

‘Smog’s heavy today.’

‘Yes, it is,’ I said, doing my best to be friendly despite the thudding pain in my head. He touched his cap in salute and I smiled at his lovely old-fashioned manners. I hoped some things from the past would stay with us.

‘Would you like a cup of tea to warm the bones?’ He reached into a leather bag and took out a flask. ‘My sister sends me honey from her own bees. It’s nicer than the daily teaspoon of sugar. Better for you too.’

‘Yes it is,’ I said happily. ‘That would be very nice.’ I loved the taste of honey and you didn’t see it all that often.

‘Good.’ He pulled another chair over and poured warm nut-brown tea into a cup. The tip of his tongue pushed between his lips as he concentrated, spooning bright yellow mounds from a jar to the cup and stirring five times in each direction. He took such pains with it.

‘Thank you. And you must call me Jane.’ I tasted the brew. He was right, the rich honey made it taste far better than the few grains of sugar we were allotted each day.

‘And I’m Albert.’ He blew on his own cup. ‘My grand-daughter’s called Jane as it happens.’ He put his hand inside his jacket and drew out a wallet of photographs. There was one of a little girl playing the violin

. She had the same tongue-between-the-lips expression of concentration.

‘She looks very good at that.’

‘She is. She’s going to one of the special music schools soon.’

‘Oh, I’m sure she’ll love it there. I’m a teacher and someone I used to work with is at one of those schools now. She says they’re wonderful – the children really flourish. I rather wish I were that age again so I could keep up my clarinet practice; I was never conscientious enough.’

He chuckled. ‘Children. They never change.’

‘No they don’t. No. But music is such a gift. Maybe one day I’ll be able to hear your granddaughter perform.’

‘I hope so. You and your husband can be her first audience.’

‘Yes we could.’

‘Then one day when you have a child I can come to his recital.’

I drank a little more as we looked through a few more photographs and talked about his four grandchildren. He was so proud of them all. ‘Now, thank you so much for the tea,’ I said after a while. ‘I have to go up to the surgery.’

‘It was nice speaking to you. Mind how you go.’

‘You too.’ I waved as I began to climb the stairs.

A welcome surge of warmth drifted over me as I reached the top of the stairs and entered the surgery. Charles, Nick’s secretary, was staring out the window.

‘Mrs Cawson. I’m sorry, but Dr Cawson isn’t here,’ he said, moving to his well-ordered reception desk. It had a little wooden block with his name, CHARLES O’SHEA, on it, that he had pestered Nick for. Charles was always neatly turned out, his fine hair flipped artfully over on the left side, but his figure was squat and somehow shapeless.

‘Oh.’ It hadn’t crossed my mind that Nick wouldn’t be there to sit me down and help me stave off the pain.

‘You should probably call first next time.’

‘Yes, you’re right.’ I looked at him keenly. I always felt self-conscious in front of Charles. ‘Where has he gone?’

‘He went out for a walk,’ he said, comparing two sheets of paper on his desk. He appeared to have some sort of unpleasant rash on his left hand and when he caught me looking at it he put it in his pocket.

Liberation Square

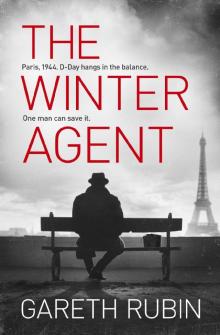

Liberation Square The Winter Agent

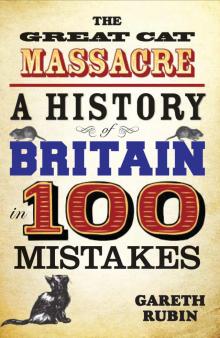

The Winter Agent The Great Cat Massacre

The Great Cat Massacre