- Home

- Gareth Rubin

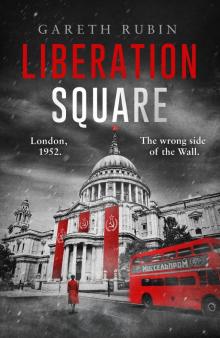

Liberation Square Page 21

Liberation Square Read online

Page 21

I tried to settle down but a noise outside made me sit bolt upright. It was shouting – too far to hear distinctly, but not distant. Somewhere in our street. A banging sound, like a door being thrown open. There was more shouting and the sound of a car door slamming before the vehicle was driven away. Nick had woken up too. We heard a desperate knocking on someone’s door. No answer. A voice calling out. The knock moved to a different door. Then another one. ‘We can’t get involved,’ Nick said. ‘Not now.’

There are many types of loss. Loss of a child. Loss of one’s dignity. And loss of what you used to be. We used to be generous. We used to look out for those who lived beside us.

26

Nick went out with Hazel the next morning to spend the day with her, to talk about her mum and give her a chance to grieve properly. She hadn’t even had that yet. ‘I almost wish she had a bit more of her mother in her,’ he had said to me. ‘Frost inside. Instead, she’s like you. A warm Victoria sponge.’

‘Do I take that as a compliment?’

‘Probably best to.’ I tried to look stern but found myself unable to do so.

Just before ten o’clock, as I was sweeping the hallway, I answered a knock at the door to find a young policeman in uniform. There was a cardboard box at his feet. ‘Is’ – he checked a slip of paper in his hand – ‘Dr Cawson here?’ he asked.

‘No, he’s out. I’m Mrs Cawson.’

‘Are you? Well, I’m handing something over. Some items, taken from … Mrs Cawson, you say?’

‘Yes.’

‘Second wife?’

I became instantly self-conscious. ‘Yes.’

‘Right. I see. These were taken from the house of … another Mrs Cawson.’ He looked at me with … with what? Pity? Disdain? I couldn’t tell. He must have thought that I was the next one on some conveyer belt of wives. Or maybe he was Catholic, a relic from the old era, and disapproved of remarriage at all. It was hard to tell. ‘It’s the stuff we took away for fingerprints ’n’ that. Couldn’t find any.’

‘I’ll see that he gets them.’

The possessions had mostly been taken from her bedroom and bathroom. I supposed it was anything that might have been touched by whoever had been there. Her identity card was on top and underneath it a few items of clothing, a glittering red lace mask of the type ladies once wore at society balls, tied on with ribbon of the same shade, a red gown made of silk – the one she had worn on the poster for The Lucky Lady, I thought – a pair of ashtrays, a long-player recording of one of Lorelei’s plays in a paper sleeve, an ivory-inlaid cigarette lighter and a bottle of her perfume. A few cheap romance novels made my eyebrows lift – she led such a glamorous life, there was surely little reason to live another one vicariously through the pages of a shilling-book.

Flicking through, I found that they were not all classic romances either – a couple were American ‘pulp’ that mined the seamier side of life in the United States. The cover of one showed two girls with long hair tussling on the floor of a women’s prison, their skirts riding up to expose their thighs. Another was set in the Roman Empire, although The Lusts of Rome looked little like the history books I had read at school. Tucked in the corner was a stack of letters, with all the envelopes torn open. I couldn’t help but pull out their contents. A few bills; some fan mail forwarded by her acting agent; and a thick card with a gilded edge. It was an invitation, the rippled-edge, copperplate-script type that had once been for elegant weddings before they were denounced as bourgeois frippery.

You are cordially invited to join the party at Mansford Hall, Fetcham, Surrey. Masques from eight until midnight. Tuesday, the 25th of November 1952.

That was four days away. Those, and a telephone number at the bottom, were all the printed words, but there was more – a strange postscript scrawled at the bottom in near-illegible handwriting, as if the writer were in the grip of pain:

Nick knows you’re selling him out

Nick. Seeing his name there felt like a blow. The card had arrived in an envelope postmarked the day before Lorelei’s death, so whatever was between them hadn’t completely ended until her death after all. ‘Selling him out’? What did that mean? I searched through the rest of the box, pulling out lipsticks, silk scarves and pill-boxes; yet nothing else made mention of this gathering. Without thinking, I picked up the telephone. Nick’s surgery was on our exchange so I dialled straight through.

‘The consulting rooms of Nicholas Cawson, Charles O’Shea speaking.’

‘Hello, Charles, it’s Jane Cawson.’

‘Mrs Cawson,’ he said.

‘Is …’ But what would I say to Nick? Would I demand to know about the note and what it referred to? It was something to do with their black-market business.

The line hissed.

No, I should wait and calmly work out what to do. And one thing was certain: she was dead now, so it was truly over.

‘Mrs Cawson?’

‘Yes.’

‘Your husband isn’t here.’

‘No?’

‘No, he is out with his daughter.’

‘Oh, yes, yes, of course. I’ll speak to him later. Goodbye.’

I hung up and looked at the invitation again. There was something about it that was magnetic too. I had never been invited to one of these events; they existed for me only in the pages of Jane Austen or Baroness Orczy.

I opened the box again to find a few more unremarkable letters, and one envelope different from the rest. There was neither a stamp nor an address on it, only a single name: ‘Crispin’. It held something solid and I ripped it open to find a slim paperback book: a copy of Sheridan’s bawdy School for Scandal. Just her sort of thing, I imagined.

I opened the book. Tucked inside was a slip of thin paper with a smudged stamp that read: ‘Citylight Prints, 2a Hannson Street, London W1’. It was dated five months earlier. There was also one of those ‘this belongs to’ gummed labels on the inside of the cover, sporting her spiderish handwriting, and when I traced over her name with my fingertips I noticed something: ridges under the label that told me there was something concealed underneath. I couldn’t help being intrigued.

I tried to scratch back the label with my nails, but it was stuck on too firmly and tearing it away could have damaged whatever lay below. A sharp knife was also unable to lift it safely, so I had to resort to the kettle to dampen and melt the glue. The label slowly curled up, lifted by the blade, to reveal an item around which the glue had been carefully laid down so as not to stick it to the page.

It was a little square negative from a camera film. I gently brushed dust from it with my sleeve, put it to the light and squinted. The head and shoulders of a figure emerged – ‘Crispin’, I presumed. I could just about see that he had a slim face, glasses, neat mid-length hair parted on one side, but beyond that it was impossible to make out anything else. It was strange that Lorelei would have a negative of this man’s image. It certainly didn’t seem to fit with anything that I knew of their scheme.

The woman had so many secrets. Every time I thought I had discovered her, there was another layer below.

I took the box to our room, lifted out the backless red silk dress and held it in front of myself, looking at it in the full-length mirror. The silk was a type that wrinkled and crinkled to give it texture, not the smooth style that had been the norm before the War, and was the same deep red as her hair.

That afternoon, I passed Leicester Square’s bronze statue of Kim Philby. His figure, poring over the lists of suspected Fascist sympathizers that he had personally handed to Beria, was dull in the lacklustre morning light. The pub opposite was named the Archangel and, as I walked under its sign showing the battleship floating on a serene Thames, I noticed a tin hoarding nearby covered with posters. One was an old bill for Victory 1945, but it was only half the poster, ripped off in the middle. Although the head and shoulders of Lorelei’s on-screen boyfriend were still wrestling with a Gestapo officer, she was gone from it, no longer inciti

ng a crowd to stand up to the Nazi occupiers. It seemed that when she had been dropped from the pages of the Morning Star four years ago, she had also been torn from the walls. Nick had once told me that the reason we had to hand in our newspapers at the end of the month was not only to reuse the paper; it was also to ensure that the only records of the past were in Somerset House. Can you rewrite history? Well, it seemed that we were trying.

Now I was in a district that I didn’t know well and didn’t want to. Shabby doorways were hung with strips of beads or gaped like broken mouths, and the tiles leading into them were broken and dirty. Some had small handwritten signs beside the doorbells. ‘Jenny’. ‘Roseanna’. I checked the street name against the address stamped on the slip of paper I was clutching and turned reluctantly down what looked like little more than a dead end. There I saw the shop. Citylight Prints was a dingy place in a dingy little street. The glass of the windows was covered with brown paper so that you couldn’t see in, which didn’t bode well, and the flaking shop sign had once been blue but now had hardly any colour at all.

‘You all right, love?’

I turned to see a striking-looking woman with strawberry-blonde hair twisted up in the French style, standing in a shop doorway on the other side of the thin lane, tapping ash from a cigarette in a long holder, the sort they used before the War. ‘You going in there?’

‘I think so.’

She took a drag. ‘You don’t look the type. You do know what it is?’ I gazed at the painted sign. ‘You don’t, do you?’

‘A printer’s?’

She hooted. ‘That’s what they call it. They do print stuff, there, love. Photos. Special type of photos.’ I could tell what she was getting at. But why would Lorelei want to get that strange negative developed there? ‘Sure you want to go in?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘If you say so.’ She pointed towards the shop with her cigarette. ‘But if he gives you any gyp, you come out to see me.’

‘I’ll do that. Thanks.’ I strode over and pushed through the strings of beads in the doorway.

It was a dimly lighted den, and the sole customer was a man in shabby clothes flicking through one of a set of boxes that lined the walls. As soon as he saw me he immediately left. I could hear a printing press thundering away in a back room. Behind the counter stood a young man, with little pictures tattooed on his neck in green-turning ink. He looked me slowly up and down, making me intensely uncomfortable, and wiped his mouth. ‘You looking for work?’ he said.

‘No.’

‘What, then?’

‘I want a print from a negative.’

He shrugged. ‘All right. Let’s have it.’ I handed it over. ‘How big?’

‘What’s the standard size?’

‘Whatever takes your fancy. Ten by eight’s normal. Centimetres,’ he said.

‘That’s fine. How much?’

‘Eighty pence. Payable now.’

‘Eighty pence?’

‘Very discreet service here. You pay for that.’

I reluctantly agreed. ‘A friend of mine recommended you.’

‘Oh, yes?’ he said with a chuckle.

‘Lorelei Addington.’

For a split second he stared at me. Then he smiled. ‘The actress? Don’t think we’ve had her. I’d be on some beach in the South Seas smoking fat cigars if we had. Lot of trade on that.’

I couldn’t tell if he was hiding something from me. ‘When will it be ready?’

‘Tomorrow at three.’

‘All right.’ I lifted it up. ‘Can you tell me anything about it?’

He looked bemused. ‘Like what?’

‘Anything.’

‘It’s a neg. What the fuck else is there?’

‘Sorry. No, that’s fine.’ I don’t know what I had expected him to tell me. As I pushed through the doorway, I glanced back. His expression showed an animal wariness.

27

I went down the stairs barefoot the next day, Saturday, thinking that we could make pancakes for breakfast and pretend it was Shrove Tuesday – I had a little sugar and a lemon to squeeze over them. Pondering whether I had enough powdered eggs, I heard the postwoman arriving. ‘You’re up early,’ she said, as I opened the door.

‘So are you.’

‘My job, though,’ she chuckled. ‘Sorry, looks like bills.’ She handed over two brown manila envelopes before touching her cap and leaving. I put the malignant envelopes on the little table in the hallway for Nick. He could deal with them. It was then that I noticed something was missing.

A framed photograph that my friend Sally had taken of us as we had left our wedding ceremony wasn’t in its place on the wall, even though the hook that had held it was still there. I searched around for the photograph and quickly spotted it on the floor by the coat rack. It couldn’t have just fallen, certainly not to where it was now. It was a little strange, but I didn’t think much of it.

As I bent down to pick it up and replace it in its spot on the wall, however, I noticed something underneath. It was a short white cigarette butt, the tobacco burned away. Nick’s brand had a sky-blue band around the white, and there was none on this one. I had thoroughly cleaned the hallway just yesterday too, and was certain it hadn’t been there then. Had someone smoked it and dropped it there, placing the photograph over it to ensure that it was found? It was said that the Secs did such things to disturb and intimidate. Or perhaps it was nothing and I had simply missed the cigarette when cleaning. I held it in my fingers, my pulse racing.

The waiting room of the South London Hospital seemed to cater to everyone without the right connections. Nick could probably have had me seen at Guy’s alongside Party members if I had asked him, but I wanted to keep my visit to myself for now, because I was there to find out what had caused my miscarriage and I wanted to know whether it was good or bad news about having another child before I told him. He was doing his usual Saturday-morning surgery, so I hadn’t had to come up with an excuse for where I was going.

There was a mass of people waiting at the chaotic reception desk. If there had ever been a single queue, it had long since broken down into an unruly shambles of young and old: aged women with walking frames crying at the back because they were too frightened of the pushing and shoving; young men forcing their way forward with hard looks; girls holding shrieking babies. Sometimes the nurses would wave at a young soldier who stood smoking by the doors, and he would amble over, bored, and push one or two of the young men outside, telling them they wouldn’t be seen. After getting to the front and putting my name down, I was directed to a hard bench, where I waited to be called. I sat watching the sea of people constantly change yet remain somehow the same.

Three hours later – I wished I had taken a book with me – my name was shouted out and I was directed to a cubicle formed of curtains within a large room with a dirty floor. There were ten other examination booths; all were occupied and in some I saw women in various states of undress attempting to cover themselves as best they could with blue sheets. Yes, it was in a bad state, but it was free, I reminded myself. It was free for everyone in need.

A tall, slim man with untidy white hair hurried into my cubicle, checking a sheet on a clipboard. He had a harassed air about him. ‘I am Dr Clement,’ he said in a French accent. I guessed he was one of the refugees from ’40 who hadn’t returned to their ravaged land. ‘May I have your name?’

‘Jane Cawson.’

‘Good, now what seems to be the problem?’

‘I had a miscarriage.’ It was the first time I had pronounced the words, and I hated every one.

‘Oh.’ He sat down and looked grave. ‘I am sorry. When did it happen?’

‘A month ago.’

‘I understand,’ he said, thoughtfully, noting down some details on an index card.

‘I want to know what caused it.’

‘What caused it?’ he repeated.

‘Yes. I want to have another child so I want to know.’

/> He looked a little troubled. ‘Please tell me the details of the pregnancy.’

I told him, keeping my voice low so that it wasn’t shared with the occupants of the adjoining cubicles. At the end, he took off his glasses. ‘Mrs Cawson, it is probable that nothing was the cause of the miscarriage. I am very sorry. It is something that happens sometimes. It is not your fault. It just occurs.’

‘Has it … damaged me?’ I asked.

‘For becoming pregnant again?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, there are tests.’

‘I would like them, please.’

‘Of course. I will first take a blood sample and a urine sample to see how healthy you are in total.’

He searched through a desk and found a jumble of instruments, including a hypodermic needle that he cleaned and sterilized in a jar of liquid. He fitted it to a syringe, rolled up my sleeve and drew out a line of my blood. ‘Good,’ he said, holding the tube up to the light. He labelled it and put it on his desk. ‘Now, here is a pot for the urine.’ He wrote on an envelope and placed a small glass phial inside it. ‘Please hand it in at the desk outside and make an appointment to come back on Monday, I will examine you properly then.’

On my way back to that seedy print studio in a Soho backstreet, feeling my way through the thickening smog, I tried to guess what I would find there. There was no indication that it related to Nick and what he and Lorelei had been involved in. It was something personal to her. Something involving a man named Crispin, whose name had appeared on the envelope containing the negative. But still I wanted to know.

Inside the shop, the man with green tattoos on his neck greeted me. ‘Got it here,’ he said, reaching under the counter. He handed me a paper bag and I drew a print from it. It was so confusing. The face on the picture was one I knew, and yet it had changed almost beyond recognition.

The thick-framed glasses were unknown to me. But the face. You could hide Lorelei’s red curls under a side-parted gamine wig but you couldn’t disguise her delicate face. ‘That do you?’ he asked.

Liberation Square

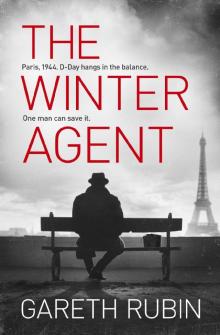

Liberation Square The Winter Agent

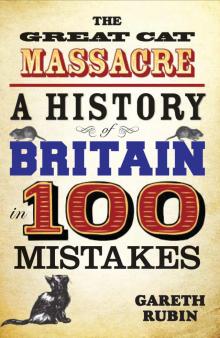

The Winter Agent The Great Cat Massacre

The Great Cat Massacre